This is an attempt to make some assumptions and chains of reasoning explicit. This piece describes pressing problems for which I have not yet reached a satisfactory conclusion.

These problems stem from: my belief in a transcendent, redeeming metaphysical order (God);1 my character shortcomings; my inability to overcome those shortcomings on my own; and my inability to subordinate my own reason to a body of tradition.

The present historical moment is marked by great breadth but a lack of depth. There is a great deal of information available to us, but we do not know how to use it to cut to the heart of our human problems and arrive at last on solid ground.

Some Definitions: Pre-modernism, Modernism and Post-Modernism

Pre-modernism – Knowledge of what is right and true comes from tradition and authority. Think of: papal infallibility, the divine right of kings. The tradition of the group you grew up in is the self-evidently correct one.

Modernism – Knowledge of what is right and true comes from reason. Society can be organized from first principles. Think of: liberalism, whig history, Marxism, the French revolution, the materialist-scientific worldview.

Post-modernism – Seemingly objective first principles put forward by modernists turn out to be more ideologically loaded and arbitrary than they first appeared. There are no first principles that exist in a vacuum. All theory, morality, language and cognition itself rest on pre-theoretical, cultural and ideological assumptions – and are open to charges of being arbitrary constructions for the benefit of those who make them.

Post-modernism reminds me of Buddhist metaphysics, where nothing exists independently in itself but is dependent on a causal chain of factors that stretches backwards and outwards in all directions ad infinitum. We look for the neutral, indisputable ground of axiomatic first principles do not find it. The sense of vertigo is immense.

I think all of these historical-intellectual stages have some important insight:

Pre-modernism: systems that have evolved over time are often finely calibrated and balanced to avoid disaster in ways that cannot be replicated from first principles. For this reason, deviating from tradition is extremely unwise.

Modernism – We have hacked reality in ways that have given us unparalleled prosperity and security. Consider the victories of the scientific-materialist worldview in germ theory and the agricultural revolution.

Post-modernism – Attempts to re-engineer society according to reason have produced horrors – such as the totalitarian ideologies of the 20th century. Additionally, reason and science have failed at providing coherent, formal models which justify themselves from first principles. Even the foundational principles of liberal democracy, the victor ideology of the 20th century, are not obvious or non-arbitrary but simply spring from the historical experiences and interests of their founders.

The Analogy of the Missing Micro-Nutrient

There is an analogy that I read in Slate Star Codex (I can’t find the original article) and it goes something like this:

People sought to distill everything that a healthy, functional human being needed into a single mass producible food. Inevitably, this project failed. It always turned out that there was some seemingly unimportant trace micro-nutrient that turned out to be vital to human flourishing that was not included. Normal human diets provided for it, but the universal food did not. The best way of nourishing yourself continued to be eating real food, and, what’s more, the kind of food that your ancestors ate for generations.

Systems which accumulate over time and come to us through the filter of survivorship often account for things we would never think of.

Tradition

There is a difference between pre-modern and post-modern traditionalists. Pre-modern traditionalists believe that their particular tradition really is the one obvious and correct way and that those outside of it are barbarians, heathens or infidels.

Post-modern traditionalists are likely to acknowledge that the first principles of traditional systems are constructed, non-universal, and in some sense arbitrary. But what matters is that they work. They are finely calibrated to give human beings what they need and to avoid disaster.

Post-modern traditionalists are LARPing as pre-modern traditionalists, as if they had never eaten the fruit. This is understandable and perhaps even excusable: they are looking for the last things that made sense in a time of dissolution and upheaval.

Spirituality and Religion

“We know that salt is indispensable for our physiological health. We do not eat salt for this reason, however, but because food with salt in it tastes better. We can easily imagine that long before there was any philosophy human beings had instinctively found out what ideas were necessary for the normal functioning of the psyche.” – Carl Jung

Every culture in human history practiced some form of religion. There are examples of something resembling materialist skepticism even in antiquity, but they are few and far between.

The deep roots of the spiritual in the human psyche suggest that it is adaptive. Its absence can cause deep suffering.

I believe religious feeling points towards something real and is not simply a evolutionary-cognitive misfire. I believe in God. I could be wrong about this. God was the only thing that saved me in the abyss, and if I am wrong about God it doesn’t really matter if I’m wrong about anything else. I can’t come up with any better answers.

But we must reckon with the diversity of religions, their apparent incompatibility, and the rendering of many of their historical truth claims implausible or false by modern knowledge.

Religion, Ideology, and the problem of belief

Both the premodern and postmodern traditionalists point out that, in the absence of an actual religion, all sorts of crazy ideas come in to fill the void. Totalitarian movements in the 20th century certainly bear this out.

I understand the strong version of this argument to be this: you are going to be in the grips of some larger system of meaning of one kind or another. Better one of the ancient ones that confines its spiritual aspirations to the spiritual realm instead of wrongly and dangerously trying to create utopia on earth.

People need a stabilizing narrative or worldview to inhabit, and, what’s more, they don’t simply construct it themselves ex nihilo. If you do not join one of the stable, old cults you risk joining one of the new ones which are far more likely to be extractive and abusive.

But “believe in the old religion or horrific new heresies will rise up to fill the void,” even if true, does not automatically equate to “the old religion is true.”

Believing in religion is not the same as believing a religion. This is especially true for universal religions, which do not claim their religion is true for a given people at a given time, but objectively true, for everybody.

I do not believe in noble lies. Even if I did, a noble lie would only be something you could convince other people of, not yourself. Belief is not a self-willed act or a free choice – we are sometimes compelled to disbelieve what we wish were true, and to believe what we wish was not.

A religious community can be flourishing and healthy despite (or perhaps because of) having some implausible and odd foundational beliefs. Mormons are often successful and happy, and yet it is difficult for a non-Mormon not to conclude that the claims of Joseph Smith are a bit suspect.2 Through the power of memetic evolution or by the grace of God even religions of dubious provenance may nonetheless produce individuals of great insight and virtue.

Christian, Islamic, Hindu and Jewish traditionalists all make arguments against modernity. But the doctrinal claims of these religions are often mutually contradictory.

Religions do provide many of the things that their adherents claim they do: a risk adverse moral framework for a fulfilling life, the exclusion of many dangerous and destructive ideas, a supportive and intimate community, and (sometimes, I believe) genuine access to the numinous.

Some of the things they demand in exchange include: public adherence to beliefs which appear implausible, an exclusion from consideration of other faith claims and ideas, and restrictions on behavior and association which may seem arbitrary.

The lifeworld built up around a set of religious claims is a thriving eco-system of meaning that works despite or because of dubious first principles. It can be the basis for an entire civilization.

The failure of ideology

Many people seek to substitute religion with ideology. In the absence of the transcendent, ideology provides a clear purpose to life: re-organize society to reflect your values.

Modernist ideology fails to answer an important question – what would you do if society already reflected your values? What if all of your reformist goals had been accomplished? The zeal for social transformation is often a way to avoid the question of what to do with surplus freedom. The ideologue seeks to re-arrange the component parts of a dead machine, imagining that this will make his actions meaningful.

SBNR/New Age: a hyper-syncretic folk religion

Folk religion emerges organically from what people on the ground actually do and believe. It is not formal, codified religion with a clear creed, set of doctrines, and authorities. Many people practice folk religion and formal religion alongside each other. Someone who diligently attends mass while also honoring the shrine of Santa Muerte is practicing both. There are large chunks of the world’s population for whom folk religion is a major or even the dominant aspect of their spiritual lives.

WEIRD people who find themselves unable to accept either traditional religion or the materialist-secularist worldview may turn to the folk religion of their society. This is the folk religion of the spiritual but not religious (SBNR). It ranges from very deep reflection all the way to love spells sold by dubious grifters.

SBNR is an attempt to relate to the spiritual outside of the confines of a formal religion. It is a hyper-syncretism consisting of everything “spiritual” that a modern person might have access to in the global marketplace. You can start the day with your mantra practice, drive off to a 10-day vipassana retreat and then fly away to do an ayahuasca ceremony with a genuine Amazonian shaman.

For the most part, SBNR lacks the rigidity of behavior and belief of conventional religions and also lacks the guiding normative frameworks. But it is too broad to be reduced to just one set of tradeoffs. Some SBNRs pursue a diffuse and eclectic spiritual practice which incorporates shallowly adopted practices from very different cultures. Others may take a more focused and restricted approach that is more like formal religion.

SBNR does not appear satisfying to me. One reason for this is that I am an undisciplined, uncreative person who, left to his own devices will spend too much time on the internet.

But beyond that, the few people I have met who seem like they have all achieved “full satisfaction” were believers/practitioners in a formal religion. I have not met any SBNRs who seem like they have achieved this. But being religious instead of SBNR is no guarantee: there is no shortage of lacklustre and uninspiring religious communities out there held together only by inertia.

Abstraction and Representation

We use abstractions that lack a one-to-one correspondence with actual phenomena but are “good enough” to be used for most decision-making. We know that at a more fundamental level the laws of the universe are non-Newtonian, but it would be dumb to try and describe the movement of a ball or a car at the quantum level.

We really have no choice but to interact with the world through these abstractions. This is only dishonest if we lie to ourselves and others about their limitations, treating them as closer to reality than they really are.

There are real things that defy precise description and categorization. We cannot pin them down precisely in words. Our day-to-day language is ill-adapted to such a project. It is better to construct allegories or works of art that point to these semantically elusive (non) entities. When we encounter a paradox, it is not a sign that reality has failed, but of the inadequacy of our conceptual language.

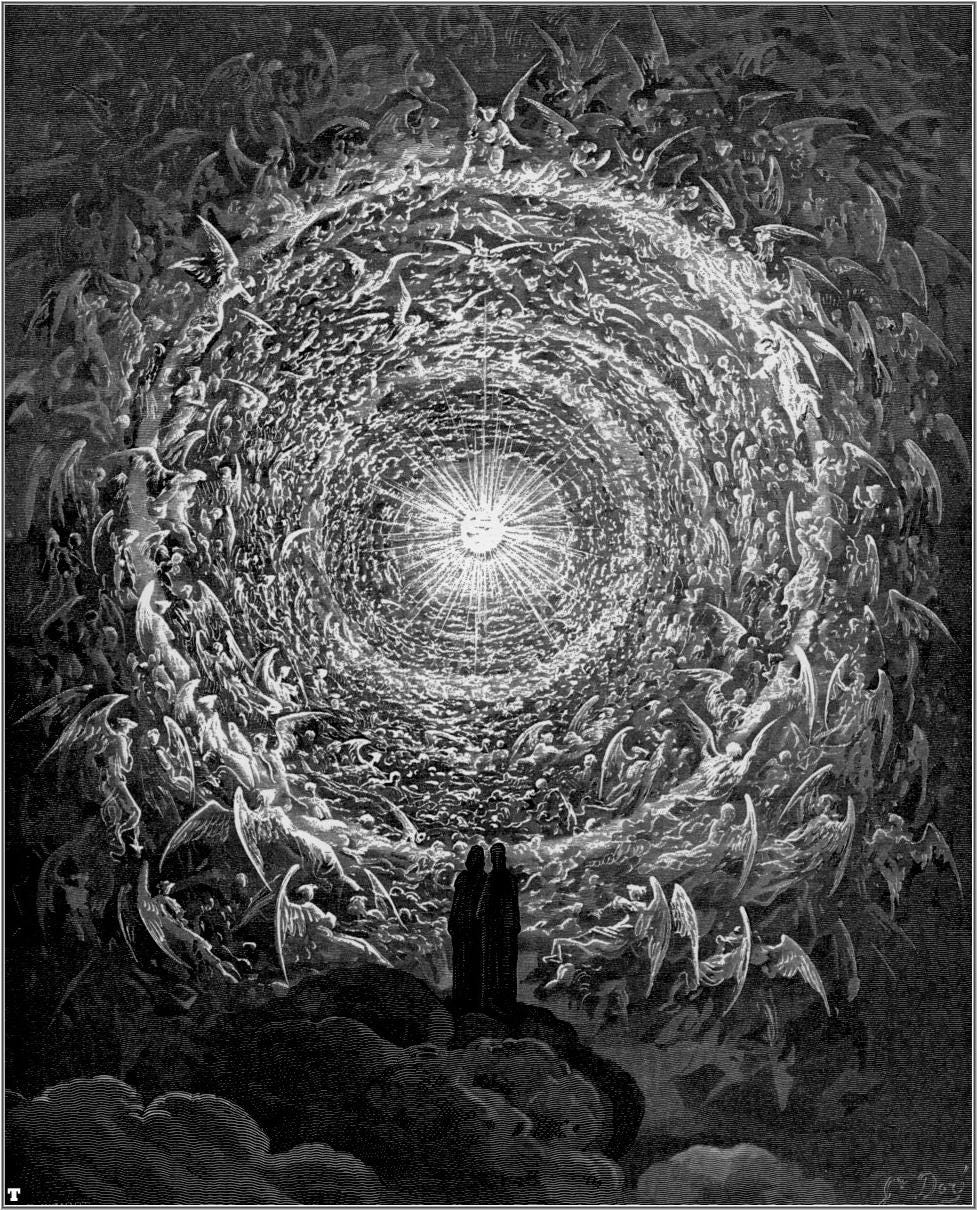

The transcendent is something that we can only feebly gesture toward, not something we can readily convey in ordinary language.

Abstraction, Perennialism and Tradition

Epistemic status: I have a limited, not a deep knowledge of perennialism and the traditionalist school.

One way to rescue a religion from dubious historical claims and charges of cultural and political arbitrariness is to see it as a finely tuned system that points towards the transcendent – but that it is also a representation, subject to human conceptual limitations. Any given religion is important and valuable, but also a crude, flawed stopgap in the task of reconciling the human and the transcendent. The signal is always shrouded in the noise of human drama.

Perennialism asserts that religions have a common orientation towards a transcendent reality despite outward differences. It points to commonalities in religious forms. Among perennialists, there is a group called traditionalists who argue that the correct response to the diversity of religious forms is not to try and step outside of them but to remain within them.

Traditionalist-perennialists see religions as Traditions handed down to humanity, Traditions which are appropriate to the people amongst whom they appear.

I think this is the wrong frame for appreciating tradition. Tradition is not a timeless form, but an evolved structure, containing the wisdom of countless dead ends cut short. It does not descend from on high down to earth, but reaches up, like a plant towards the sun. But this is at odds with the self image of religions that posit themselves as complete, perfect divinely disclosed revelations.

The transcendent as micro-nutrient, religions as traditional diets

The transcendent should be understood as the missing micro-nutrient of (post) modernity – a micro-nutrient which is also toxic in inappropriate doses. If the depressive disenchantment of modernity is caused by too low a dose, some mental illnesses may be the result of too high a dose. Traditional religions are the ancestral diets which give us the appropriate levels of this micronutrient for human flourishing.

The point of tradition is that we cannot discern which parts of a complex system are important using our reason alone. When we strip away the “irrational” parts of a religion, we can end up with something bland and un-nourishing.

A religious conversion that deeply changes person’s character is rarely to one of the refined “rational” religious variants. Not very many people become Unitarian Universalists on death row. It is more likely to be something old school with a whiff of fire and brimstone. This is not surprising: a genuine encounter with the transcendent is astonishing and transformative. It is less like a philosophical insight and more like seeing a dead man rise up and speak to you.

Confession

I believe in God. I came to this belief by using psychedelic drugs.3 My psychedelic experiences closely resembled a classic religious conversion: hitting rock bottom, repenting, and finding a redemptive power outside of myself. The best description of this process I have found is in William James’ “The Varieties of Religious Experience.”

Intense religious experiences are not ends in themselves. We should not be endlessly repeating the ecstasies of this initial encounter but answering its call to live differently. A religious experience, psychedelic or otherwise, provokes the question: “how should I live in light of this knowledge?”

The changes in my character produced by these experiences are transitory and fleeting. I vow to change but always backslide into being hard-hearted and selfish. When I see my “normal” self clearly I see a gollum-like creature consumed by craving. And yet there is also something more noble trying to get out. I must find a way to live that keeps me vigilant and awake.

Christianity

I tried to write this piece in a way that was applicable to all religions. But you may have noticed Christian themes and vocabulary. Christianity is the religion of my culture.

I see in Christianity a complete redemptive stance towards the human condition. But I have difficulty affirming some things that most Christians regard as core articles of the faith.

I am not satisfied that the Resurrection and Virgin Birth are historical certainties. I am also aware that core doctrines of Nicene Christianity are the result of decisions by early Church councils. It is not possible for me to pretend that they are immutable metaphysical facts revealed by divine revelation.

I do not believe that it should be essential to believe these things. I believe the scriptures and the Christian tradition testify to a redemptive stance towards a fallen world. This is the real kerygma that makes Christianity fascinating to me. It is not reduceable to a secular moral philosophy: it makes sense only with reference to the genuinely transcendent. But neither is it synonymous with orthodox Christian doctrine. Christianity resonates with so many because it speaks to something metaphysically true.

I am fully aware that my affinity for Christiaity could be a result of my own cultural conditioning. A stance does not mean “the only acceptable stance.”

But as a convert, I would be asked to affirm propositions about which I do not have anything approaching certainty. I cannot do this: the importance of the task demands ruthless honesty. This does not mean that those who do believe are wrong: this is something about which people can, in good faith, disagree. But expressing certainty in that which I do not have certainty is dishonest.

This problem is intrinsic to most communities: collectivity, belongingness, and sacredness are in many ways antithetical to truth seeking.

I will continue searching for a faith community which can tolerate my doubts, and whose doctrines I can tolerate, in the spirit of mutual charity and forgiveness.

Throughout I have used catch-all terms like “the transcendent” or “the numinous” interchangeably, in order to include traditions which do not have a personal creator God.

If you disagree with my assessment, substitute Mormonism with some other tradition of recent prophetic extraction: Ahmadiyya, Baháʼí, Seventh Day Adventist, etc. You will find individuals living virtuous and pious lives in any of these traditions, whether or not you believe the claims of their founders.

I realize that conclusions derived from drug induced states may invite skepticism. I have a few responses to this:

1. All knowledge, in the end, is founded on our intuitions because even the feedback of our senses is not always reliable. These experiences are among the most intuitively compelling I’ve had.

2. These drugs tend to ruthlessly point out my self deceptions and blind spots, although generally these are moral rather than epistemic.

3. Under the influence of these drugs, I have received a number of insights about my life that, after the drug effects had dissipated, I realized were entirely correct, or which neatly cut through some difficult dilemma or problem I was struggling with.

This was an interesting read and I've felt the same about a lot of these specifics...so I'm pretty sure I've mentioned this on Twitter but I'll risk mentioning again that I've realized fairly recently that Sufism may be a good fit for me for a lot of the reasons described here. Even the more traditional Muslim versions are often relatively universalist in theory, the range of schools allows for a pretty broad spectrum of beliefs/non-beliefs, and some of the more modern versions feel to me like pretty culturally appropriate natural evolutions. Though, of course, I'm sure you've also considered traditional Buddhism, which often doesn't require anything at all in terms of belief. Since it's not mentioned here at all, I'd be curious where you think that kind of tradition fits into all of this.

I think that some of what you put in post-modern was available to medieval thinkers, but it was the esoteric teaching of the religion. Part of belonging to a community of one religion meant that even personal intellectual advancement would not lead to abandonment of said community when doubts arose (and they did) but rather an understanding that different people need to hear different things.