Loss of the Lifeworld

A while back I visited a museum with an insect display and had some questions answered by a volunteer I was with. My question about the ants was: do they have a queen?

They did not. All of their activity was a pointless milling about. There was no future for them. They were severed from any context that could give their actions meaning.

This same museum had a fallen meteorite that had been a Cree pilgrimage site. It had been dug up by a Protestant missionary and found its way to the museum. The meteor, like the ants, had been severed from its proper place in the world.

The web of interlocking contexts in which things have meaning is a lifeworld. It is inseparable from, but not synonymous with, culture. The disintegration of the lifeworld is the cause of many problems.

Mechanical and Biological Metaphors

The word “culture” employs a biological metaphor: fermented foods are made with cultures. Gardens are cultivated. Living things have a continuity and a lineage. They are not assembled from component parts but are raised (and descend) from the generation that preceded them. Culture is not something that is built from an assembly kit of first principles but is something that has learned to survive in the world and transmit itself to the future. In the biological metaphor, the world is full of things with will, desire, ancestry and agency. A lifeworld is better understood through the lens of a biological metaphor. Its parts are not fungible.

In contrast to the biological metaphor is the mechanical metaphor. In the mechanical metaphor the world is full of interchangeable parts subject to universal laws. This metaphor is fundamental to modernism and the technological worldview. A world subject to universal laws is a world ultimately knowable by reason – a world that can be derived from first principles. But the mechanical metaphor is not inherently more obvious or true than the biological one. It often leads to seriously wrong assumptions about the world.

For example, wildlife biologists have discovered that populations of animals have knowledge of their environment that they pass on to their children and to other members of their group. A group of animals that has just been introduced to a habitat is in a very different position from one that has lived there for generations. Why is this a discovery, and not the default assumption? It would be more surprising if this were not the case.

The habit of some indigenous cultures to refer to animal species as “nations” – such as the wolf nation or the caribou nation – recognizes this simple, fundamental truth. Contrast this common-sense view with the skepticism that animals even have consciousness or an inner emotional life – a view that had traction within western philosophy for centuries. Even today the “discovery” that animals are highly intelligent or have complex emotional lives is sometimes reported as “news.” “Scientific,” mechanistic, and technological assumptions about the world are not epistemically or ideologically neutral – they are arbitrary and often wrong.

Western thought and philosophy are characterized by the search for universal truths that are true independent of their context, such as mathematical proofs and physical laws. This has met with mixed success: it has yielded certain technical powers, but also raised problems. The technical powers often only yield results at scale: that is, after a levelling and decontextualization has been imposed on the environment.

While the search for universally true principles might be good for some things, like generating vaccines or going to the moon, its usefulness is overrated. The “knowledge is power” cliché imagines that this kind of detached, scientific understanding of the world leads directly to mastery, like James T. Kirk making gunpowder on an alien world. People who subscribe to this view of the world – that it can be mastered with knowledge of universal first principles – sometimes excel in highly formalized domains like finance or computer science, but flounder when it is not so easy to level away real world friction and variation. The latter cases vastly outnumber the former and are more important to human flourishing.

In the same way that most people would do better to serve their nutritional needs by eating a hearty, traditional diet than by taking supplements, most people would better meet their need for meaning by living in a flourishing lifeworld – a pre-existing system of meaning - than by looking for a life mission grounded on universal first principles.

Transmission and Lineage

Religions typically place a high importance on lineage. Apostolic succession traces its lineage back to Christ, silsila back to Muhammad, and the vinaya back to the Buddha. It is an article of faith for many that without this unbroken connection to the founders, something important would be lost. This insistence on continuity makes sense from the perspective of a biological metaphor, but not a mechanical one. From the perspective of the biological metaphor, something without ancestry is a sterile, dead thing. New life might appear ex nihilo – but this is so unprecedented as to be a miracle or act of divine intervention.

Some chains of transmission are very resilient – you carry the genetic legacy of your ancestors back to the dawn of time and neither you nor your descendants will ever be free of it. Other chains of transmission are much more delicate, and their destruction may invite disaster. The legacy of residential schooling in Canada is one such example. Children were taken away from their parents with the intention of destroying the familial transmission of culture. The result was tragic and in retrospect predictable: generations of profoundly damaged people who struggle to make their way in the world. At best, the ideology behind residential schools mistakenly believed that the organic institution of the family could be replaced by cultural factories run by church and state. At worst, it was explicitly genocidal.

In human cultures, pilgrimages, relics and initiations seek to maintain an unbroken link back to the past. A holy site, the grave of a saint, or the site of a formative battle have a special meaning. The mountain where your people first received the law is not the same as any other mountain. The bones of a saint are not the same as any other bones. A lifeworld is not created ex nihilo nor uncovered by reason – it is a super-organism and an ecosystem of meaning.

The Destruction of the Lifeworld

The destruction of the lineages and sacred sites of a culture is often done with genocidal intent. This does not always go as intended. A conquered culture that mixes its own culture with that of the conqueror may produce a vigorous hybrid. Examples of this are African diaspora religions which survived (and even flourished) under harsh colonial regimes while adopting a sincere Catholicism.

Modern people are as contemptuous of their own past as colonizers were of their subjects. On Vancouver Island, I recently noticed a house being built over top of a 19th century Methodist graveyard. In 1990 the attempt to build a golf course over Mohawk gravesites precipitated an armed standoff and national crisis. Non-natives in Canada are even more indifferent to the desecration of their own ancestors’ graves than they were to those of the Mohawks. What is obvious to the Mohawks is not at all obvious to most Canadians.

Tourists who look for a spiritual vitality not found in their own culture unwittingly replicate this pattern. They want to participate in the spirituality of a culture with an intact lifeworld, but they also want to break off a piece of it and take it home with them. They collect experiences and techniques to be packaged up and taken back to their own homeland without the supporting social context. Like a flower cut from a plant, it does not survive the journey back. This same mechanistic thinking is what devastated their own culture and spirituality. They will pay thousands of dollars to visit a guru or drink ayahuasca but cannot locate (much less defend) the graves of their ancestors. They are refugees become invaders.

Members of non-indigenous, majority populations in modernized countries might not have the sudden shock of being overrun by an alien civilization, but they are engaging in a similar process of destroying and undermining their lifeworld. This produces rootless, dysfunctional individuals who suffer greatly.

Monsters of Modernity

The loss of a human lifeworld is profoundly destructive to the individual and a major source of anxiety. A lifeworld cannot be created ex nihilo, it is a living thing and its cultivation is an ongoing, multi-generational project. Desperate to return and without knowing how to do so, people create monsters.

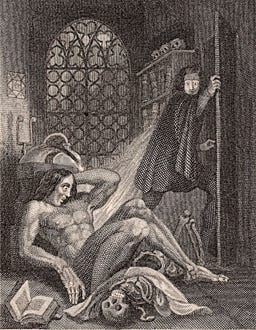

Frankenstein is the quintessential horror story of modernity. Doctor Frankenstein becomes convinced that life is something which can be created with sufficient knowledge. He is not satisfied to create life the ordinary way, but wishes to create it from first principles, from nothing. Of course, he does not create it from nothing: he pieces it together from bits of corpses. The result is something out of place in the world: a suffering and vengeful monster.

Modernity can be seen as a progressive tearing away of the masks of sacred authority which had legitimated our civilizational projects. When people looked for a successor to this sacred authority, the obvious answer was to use principles discoverable by reason. This also produced monsters: the great tyrannies and moribund dystopias of the 20th century.

People continue to look for the orientation and nourishment that has been torn from them by the collapse of the lifeworld, and they will continue to do so without a full understanding of what they have lost and what they are looking for.

Cargo Cults of the Lifeworld

“Tradition is not the worship of ashes but the preservation of fire.” – Gustav Mahler

In attempting to return to a flourishing lifeworld, people often mistakenly apply the mechanical metaphor. They may try to revive things that neither they nor their ancestors ever experienced, using old texts, first principles reasoning, and contemporary ideology.

The cargo cult approach produces an obsession with details, minutiae, and purity that is not found among people with genuinely living connections to the past. In contrast, people who inhabit living traditions often combine them with aspects of modernity without a second thought, like an indigenous hunter who combines wild meat and groceries from the store.

Converts and LARPers are more likely to obsess over the recreation of an imagined past in the most minute detail. This is a kind of cargo cultism, or an attempt to give life to something which is dead. No matter how obsessively one attends to the details, one cannot breathe life into a dead thing.

Fundamentalism is a modernist anti-modernism: fundamentalists are threatened by modernity but also compelled to reconstruct their faith to respond to modernist criticisms. The accumulated folk practices of living traditions cannot justify themselves with reason or first principles (in this case, scripture) and are an embarrassment to fundamentalists. They are sometimes prepared to do immense violence trying to return to the imagined early purity of their religion.

Living traditions mutate and permutate. They are nourished at their roots but threatened at their boundaries. A faerie-tale might have a dozen or a hundred variations depending on the teller or region. So too for a ritual, a dance, or a language. Rigid boundary enforcement is a sign of an insecurity, a fear that one’s way of life may be unrecognizably diluted, distorted or annihilated. This is not always wrong, but it is always rooted in fear.

As a European-descended inhabitant of the "New World" (so stupid to call it that, as if it was a brand new baby continent with no history at all), and someone with no religious affiliation, I have felt this disconnection all my life. I've wanted to remedy it...I've delved into Celtic mythologies and even practiced Wicca in an attempt to connect to my ancient "European" culture. I've baked butter tarts, ate poutine, and bannock, and camped in the mountains in attempt to connect to my more recent "Canadian" culture. I've flirted with going to church to connect with my "Christian" culture - I've actually been going to multiple church-events with friends of various Christian faiths since I was a child. But none of it feels like truth to me. I'm lost. I don't pretend that my loss is greater than that of people who are wrenched away from their culture (like Indigenous children); but the slow drifting away from culture is damaging in it's own right. Thanks for this piece, it really helped me contextualize what I'm experiencing. <3

Found this stimulating to read. It feels as though the past and the lifeworld have been supplanted by media and an imposed narrative at odds with observable reality to which outliers cannot resonate with.