In this post, I am not using the word ‘saint’ in a religious or spiritual sense as I did in my previous post “Saints and Monsters.” I refer instead to the secularized concept of moral saintliness.

Moral Saintliness

This post was originally going to be a response to Susan Wolfe’s essay on moral saints. I think she got a lot wrong in that essay. But I want to take the concept of a moral saint – as one who is principally and at all times occupied with morality – to examine its failures.

The moral saint is always morally scrupulous and is fixated on altruistic, pro-social moral concerns. Scrupulosity means that the moral saint does not allow himself to lapse – for example, by habitually telling lies or being cruel. The altruistic orientation means that he doesn’t abandon his pro-social orientation to pursue selfish goals – like making money or getting laid. Whether or not anyone ever has perfectly embodied these traits is beside the point – the moral saint is an archetype, a facet of human potential.

Striving to be our moral best at all times can make us miserable – depriving ourselves and those around us of our own flourishing and happiness. We should try to figure out when moral scrupulosity offers diminishing returns – when trying to be a better person is no longer worth the effort. A supremely virtuous and scrupulous life is not the best path to a meaningful life.

This is not a defense of moral nihilism! Pursuing virtue well beyond that of the mythical ‘average person’ is a good aspiration to have. Morality is a necessary but insufficient component of meaning. It becomes counterproductive if we rely on morality as our primary source of meaning in life.

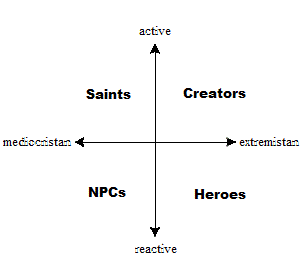

This raises the problem of what we should pursue instead. I will examine three archetypes: the Saint, the Hero, and the Creator.

Contrasting Heroes and Moral Saints

Distinct from the saint is the hero – someone who responds to a sudden crisis in a brave and selfless fashion. The hero must be “called” – typically by some external shock from the outside world. The hero is not primarily oriented towards doing or being good but towards responding to some catastrophe. The moral saint can also be called – but this call is more likely to be experienced as an inner crisis.

The hero responds to circumstance; the saint sets out to make an inner transformation. The saint aims to shine at all times – whereas the hero shines when the stakes are high. The moral saint approaches time as continuous, smooth, and fungible. Every moment is the same as every other, and so scrupulosity must be maintained at all times. Morality is approached the way a wage-earner approaches the question of wealth – as one of continuous, steady accrual. If you are familiar with the works of Nicholas Nassim Taleb, this is mediocristan.

Not to belabour the point, but I must once again cite this smooth brained example of fungible-time thinking.

Heroism is in the realm of the realm of infrequent and high impact events – extremistan. The hero experiences time in terms of sudden crises loaded with import.

Ordinary day to day scrupulosity – the kind we associate with moral saints – quickly runs into diminishing returns, because every moment is not as morally loaded as every other. We can cheat ourselves and those around us by sacrificing energy and happiness to maintaining the same level of moral scrupulosity and sensitivity to the suffering of the world at all times.

The most robust moral injunctions are negative – “thou shalt not.” There is a stronger moral onus on us to refrain from doing harm than to do good. This runs into the dead grandfather problem: the very scrupulous can find their efforts focused on things they could do better when they were dead - like not eating meat, not consuming hydrocarbons, and not lusting after their neighbours’ wives.

Moral saintliness has the advantage that it can be actively approached. We do not have to wait for some great crisis or opportunity to prove our worth. The moral saint insists that there is already a moral crisis in every-day life, one that demands a response. You might never encounter an actual drowning child, but there are statistical drowning children within financial reach of you. In contrast, the typical refrain of any 6 o’clock news hero is “I didn’t even think, I just reacted.”

The hero is ordinary but rises to nobility in a crisis. Heroes can struggle with the public perception of nobility that is placed on them after their heroic feat. When they return to ordinary life, their flaws and failings can emerge, like the one-time hero who is later arrested for drunk driving or domestic assault.

Actively trying to be heroic mostly requires cultivating neutral jing – waiting in a state of alert preparedness. Even those who seek out heroic jobs – such as first responder – find that they entail long uneventful periods broken by sudden shocks.

For heroes, the role of non-moral virtue looms larger: quick-thinking, cunning, strength, or having specialized skills in areas like combat or emergency medicine.

The payoff of heroism can be much higher than that of saintliness. The world needs heroes. The greatest consequentialist heroes of our time were level-headed Soviet military officers (and perhaps their still-classified American counterparts) who prevented wars that would have killed hundreds of millions.

The Creator and the Virtue of Selfishness

The paradox of moral goodness and individual flourishing was seen clearly by Ayn Rand: many of those who are of greatest service to others are profoundly selfish. They are driven by their creative instincts to build things whose benefits spill over onto others. Conversely, people possessed by a selfless, pro-social moral vision can be vicious tyrants.

There is still a moral floor to the project of human flourishing. For Rand it was the floor laid out by classical liberalism: respect for the autonomy of other rights-holding agents. This doesn’t mean that this is the most desirable moral level to aspire to: most of us could stand to be more virtuous. We can and should strive to be kinder, more generous, more honest and more concerned about the sufferings of others than is personally convenient.

But eventually moral scrupulosity hits the walls of diminishing returns. Focusing all of our energy on this project can leave us joyless, severe, dried up, and attaining only a fraction of our potential value to the world. In a worst-case scenario, our scrupulosity makes us harsh and vindictive towards those who have not imposed the same burdens on themselves.

Before this happens, we should turn towards living a creative and generative life, and not a merely virtuous one.

The alternative to self-abnegating morality is not base hedonism. The hedonic treadmill means that such an endeavour quickly burns itself out. Rather, the alternative is the creative selfishness that drives us to bring our vision into the world. This can have immense pro-social payoffs, but this is not the primary aim. To generate these payoffs, the creator is not loyal to the effect of her creation, but to the creation itself. Artists who prioritize creating art for other people end up producing commercial kitsch (if they are populist) or pretentious garbage (if they are elitist).

The Creator

The moral saint’s shortcoming comes from the fact that moment to moment scrupulosity is geared towards mediocristan - the low impact realm of diminishing returns. The hero’s shortcoming is reactivity – a negative focus towards averting catastrophe, which can leave him without a sense of active agency in the world.

In the positive, extremistani quadrant we have the creator.

The creator creates meaning and order where none existed before, accomplishing the apparently miraculous feat of spinning them out of the void. Where the hero is reactive, and oriented towards threat, the Creator is active and oriented towards opportunity. Where the hero is focused on avoiding catastrophic downsides from infrequent, high impact events, the creator seeks novel ideas with potentially large upsides.

Like the hero, the creator experiences time in moments of sudden impact – when ideas occur to them unbidden, manifesting out of the mysterious depths of the unconscious. Work can be done to prepare the field for their arrival, and also afterwards to render them into reality. But irregular, unpredictable flashes of insight are common and must be accepted as they arrive.

Ideas and systems of meaning have a potential to take off, even altering the course of civilizations – but there is no guarantee that they will. In the same way that ‘hero’ runs the gamut from someone who jumped into icy water to save a puppy all the way to the guy who averted nuclear war, ‘creator’ ranges all the way from a fringe blogger to the founder of a major religion.

On any job site, more useful than the hard worker is the smart-but-lazy guy who comes up with better ways of doing things. The hard worker can add to the productivity of the workplace - but the smart-but-lazy guy multiplies the productivity of the hard worker. The hard worker is the virtuous one (the saint) and the smart-but-lazy guy is the creator who changes the way work on the job site is done.

We already live inside the aggregate of systems inherited from various creators.

When we are no longer satisfied with the answers these systems provide, we strip them away until we find better ones – or, if the process goes far enough, confronting the void and coming up with our own, taking our place among the creators.

Fantastically written! The voice you write with is enjoyable and captivating for these topics. Gave me new ways to think about things I see in myself and others.

I used to live in a system where intense effort was put into becoming clean, pure saints. It was altruisitic, but purity didnt only mean no harm. It also meant spending every ounce of energy studying torah. (This is trying to shed light on sometjing underplayed in your essay- saints arent all EAs. They often hold a virtue ethics view within an ideology.)

The mains shift ive experienced from that place is that if I want to be a source of good for others, i need to overflow. Self sacrifice only works if its done in joy.

So instead of dropping saintliness, ive become wiser about it.